Bible Translations: Language, Legacy, and the Case of Maltese

The Bible is the most translated book in human history, with parts rendered into over 3,500 languages. These translations have profoundly shaped religion, culture, literacy, and identity across the globe. For billions, the Bible serves as a spiritual cornerstone and rendering it accurately and accessibly has been a monumental task spanning centuries. Each translation tells a unique story of faith, adaptation, and linguistic craftsmanship. This article explores the evolution of Bible translations, with a particular focus on lesser-known languages such as Maltese, highlighting the cultural and historical significance of each version.

Origins of Bible Translation

From Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek to the World

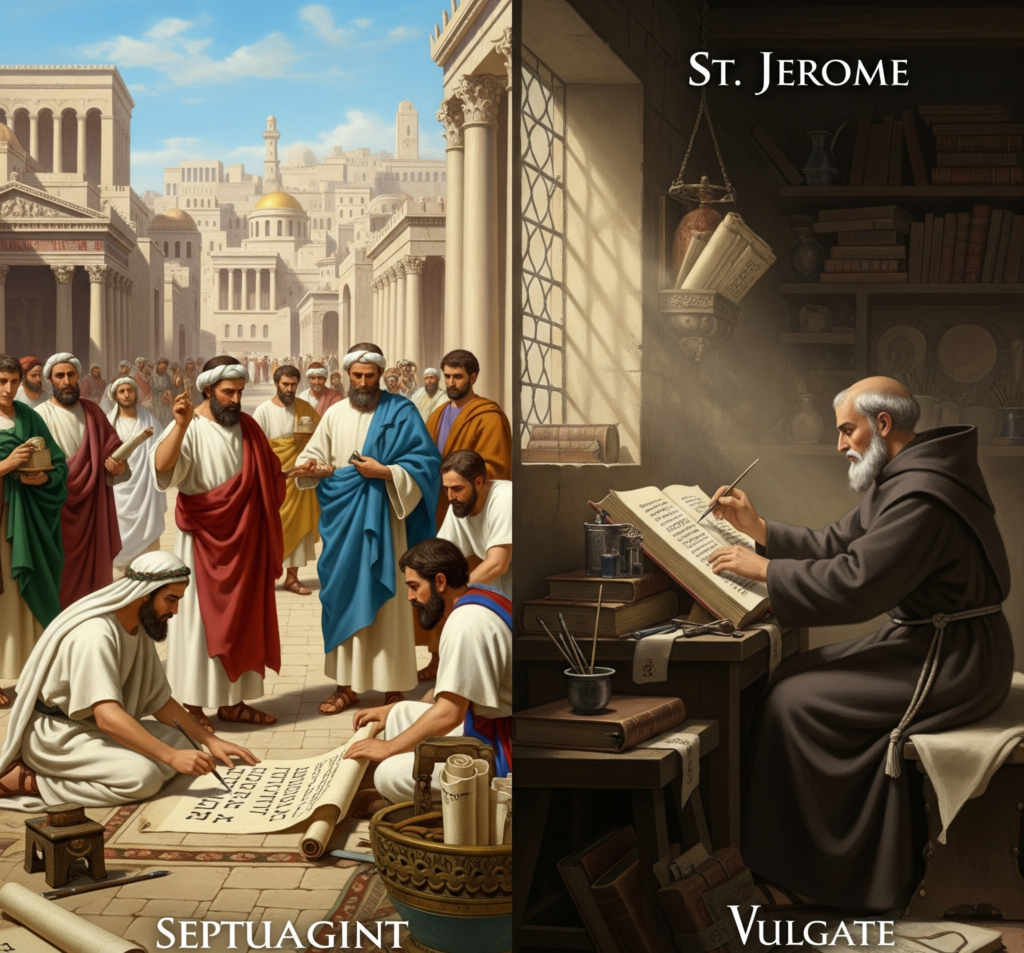

The Septuagint and the Vulgate: Pioneering Translations

The Role of the Printing Press in Bible Dissemination

Major Milestones in Bible Translation History

Martin Luther and the German Bible

In the early 16th century, Martin Luther translated the Bible into German directly from the Hebrew and Greek texts. His work was both a theological and linguistic achievement, marking a decisive break from Latin dominance and giving ordinary Germans access to scripture. Luther’s translation helped standardize the German language and fueled the Protestant Reformation by challenging the Catholic Church’s monopoly on biblical interpretation.

The King James Version and Its Enduring Legacy

In the early 16th century, Martin Luther translated the Bible into German directly from the Hebrew and Greek texts. His work was both a theological and linguistic achievement, marking a decisive break from Latin dominance and giving ordinary Germans access to scripture. Luther’s translation helped standardize the German language and fueled the Protestant Reformation by challenging the Catholic Church’s monopoly on biblical interpretation.

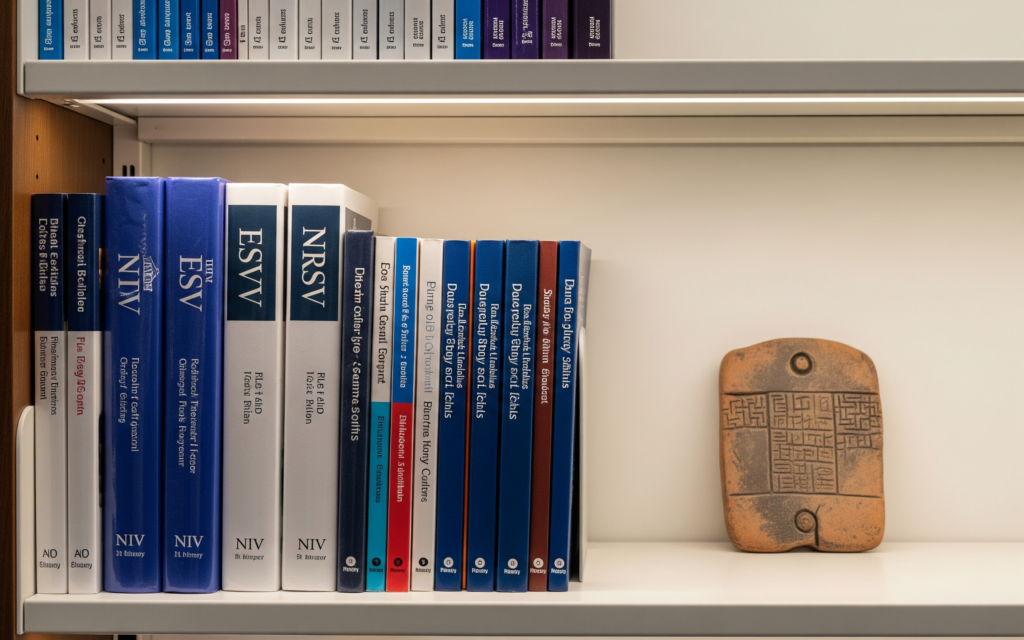

The Rise of Modern Translations: NIV, ESV, and More

Spotlight: The Bible in Maltese

Malta, with its deep-rooted Christian heritage, offers a compelling case in the narrative of Bible translation. The Maltese language, a Semitic tongue influenced by Italian and English, is spoken by approximately half a million people. Though relatively small in number, the Maltese-speaking population maintains a strong cultural identity shaped by Roman Catholicism.

The first full Bible translation into Maltese appeared in the 20th century, though partial translations and liturgical texts had circulated earlier. Notably, Pietru Pawl Saydon, a Maltese priest and linguist, produced a translation of the New Testament that emphasized clarity and faithfulness to the original texts. Translators faced the dual challenge of preserving theological accuracy while adapting the content to a language with distinct grammatical structures and idiomatic expressions. Today, the Bible in Maltese is used in churches, schools, and homes—serving both religious functions and the preservation of linguistic heritage.

The Importance of Language in Bible Translation

Language is more than a medium for communication—it carries cultural, historical, and emotional significance. Bible translators must choose between formal equivalence (word-for-word) and dynamic equivalence (thought-for-thought) approaches. Each method has its advantages and limitations, and the choice often depends on the intended audience and purpose.

Cultural context also plays a critical role. A phrase that carries theological weight in one language may have no equivalent in another, requiring sensitive and creative interpretation. This challenge intensifies when translating into minority or under-resourced languages, or in regions where Christianity is not the dominant faith. Maintaining doctrinal integrity while ensuring accessibility is a delicate balancing act that demands both linguistic and theological expertise.

Conclusion

Bible translation is not merely an academic or religious endeavor—it is a cultural and historical milestone. From Jerome’s Vulgate and Luther’s German Bible to digital tools and emerging translations like Maltese, each version embodies a convergence of faith, language, and history.

The case of Maltese illustrates that even small language communities are committed to making scripture available in their native tongue. As technology advances and global connectivity increases, the mission of Bible translation continues—driven by the conviction that every person deserves to access sacred texts in their own language. These efforts are not only acts of faith but also contributions to cultural preservation, linguistic diversity, and global understanding.

References: